Average Hospital Stay to Have a Baby in 1940

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Vaginal delivery: how does early hospital discharge affect female parent and kid outcomes? A systematic literature review

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth book 17, Article number:289 (2017) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

There is an international trend to shorten the postpartum length of stay in hospitals, driven by cost containment, hospital bed availability and a movement toward the 'demedicalization' of birth. The aim of this systematic literature review is to determine how early on postnatal discharge policies from hospitals could bear upon health outcomes afterward vaginal delivery for healthy mothers and term newborns.

Methods

A search for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and chief studies was carried out in OVID MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Econlit and the Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Dare and HTA databases). The AMSTAR checklist was used for the quality appraisal of systematic reviews. The quality of the retrieved studies was assessed by the Cochrane Collaboration's tools. The level of evidence was appraised using the GRADE arrangement.

Results

Seven RCTs and two additional observational studies were found merely no comprehensive economical evaluation. Despite variation in the definition of early discharge, the authors of the included studies, concerning early discharge and conventional length of stay, reported no statistical difference in maternal and neonatal morbidity, maternal and neonatal readmission rates, infant mortality, newborn weight gain, neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, or breastfeeding rates. The authors reported conflicting results regarding postpartum depression and competence of mothering, ranging from no difference according to length of stay to better results for early discharge. The level of bear witness of the vast majority of outcomes was rated as low to very low.

Conclusions

Considering of the lack of robust clinical evidence and full economic evaluations, the current data neither support nor discourage the widespread utilise of early postpartum discharge. Before implementing an early belch policy, Western countries with longer length of hospital stay may benefit from testing shorter length of stay in studies with an appropriate pattern. The issue of price containment in implementing early belch and the potential bear upon on the current and futurity health of the population exemplifies the need for publicly funded clinical trials in such public wellness area. Finally, trials testing the range of out-patient interventions supporting early discharge are needed in Western countries which implemented early discharge policies in the past.

Background

In Western countries, there is a trend to shorten the postpartum length of stay in hospital driven by cost containment, hospital bed availability and a motility toward 'demedicalisation' of childbirth [one]. Although this tendency was initiated every bit early as the 1940s in the United States [2] other countries followed subsequently. Thus, while the average postpartum length of stay in Swedish hospitals was 6 days in the 1970s [3] it declined to 2.3 days in 2010 [four], reflecting a like elapsing to that observed, the same year, in holland (two.1 days), New-Zealand, Ireland and the United states of america (2.0 days) [4]. In addition to shorter hospital stays, early on postpartum belch for good for you mothers and newborns was introduced to promote a more family-centred approach to nascence allowing greater interest of fathers, less sibling rivalry, improved balance and sleep for the mother, less exposure of the dyad female parent-newborn to nosocomial infections, enhancement of maternal confidence in caring for the baby, and finally, less conflicting communication on breastfeeding [five]. However, concerns about early discharge arose regarding potential adverse outcomes such every bit delays in detecting and preventing maternal morbidities and neonatal pathologies [6], earlier weaning, lack of professional back up, college prevalence of postpartum depression and increased hospital readmissions for both mothers and infants [5]. Societal concerns about maternal and newborn welfare in the context of early discharge led the United States to vote the Newborns' and Mothers' Wellness Protection Act in 1996 making it mandatory for health insurers to cover postpartum hospitalisation for a minimum of 48 h after vaginal delivery and 96 h afterwards a caesarean department [2]. Therefore, early discharge after vaginal nascence is considered as less than 48 h in the United States. However, to date in that location is no standard definition of early postpartum discharge because of large variations in the usual boilerplate length of stay for vaginal delivery between countries (i.e. in 2011, the mean length of stay for single spontaneous delivery was 5.2 days in Hungary, 4.2 in France, 4.0 in Belgium, ii.viii in Commonwealth of australia, 1.7 in Canada and one.five in the United Kingdom) [4]. Consequently, early on postpartum discharge varies from 12 to 72 h depending on the country [7].

As in some other Western countries, Belgium experiences an average infirmary stay for vaginal deliveries of 4 days. Decision makers willing to introduce earlier hospital discharge need bear witness based data virtually the effect of such policies on neonatal and maternal health outcomes. Therefore, this literature systematic review aims to decide how, early on discharge policies with or without dwelling house care (back up) touch on health outcomes subsequently a vaginal birth for healthy mothers and term newborns (≥ 37 weeks) in Western countries.

Method

Eligibility and search strategy

Studies included in this systematic review compare 'early belch of salubrious mothers and newborns after a vaginal birth with or without home care' with standard length of hospital stay equally defined in the time and place where the studies were conducted.

Caesarean sections necessitate longer hospital stays and more complicated postnatal care. Therefore, we selected all studies that included vaginal birth of alive singleton term infants with or without instrumental help. All studies must include infirmary deliveries overseen by a wellness care professional person in Western countries. Studies describing deliveries past caesarean sections, the presence of postpartum haemorrhage, substance abuse during the pregnancy, disability, domestic violence, low nativity weight, preterm baby, or dwelling birth were excluded.

Women's views about length of stay or satisfaction with care are not included in this review considering these outcomes are highly context-specific. Equally international comparisons are influenced by a wide range of confounders such every bit time, subjective wellbeing, type of care organisation… [8] and because of the lack of data regarding these confounders in the publications, the adjustment is challenging and will not exist reviewed here.

This review was conducted according to the PRISMA statement [9]. The search for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and main studies was carried out past an information specialist (NF) and validated past other co-authors in OVID MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Econlit and the Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cartel and HTA database). MESH terms and related keywords were used in an extensively searched (detailed search strategies by databases are available in Additional file i). Ii independent researchers (NB, LS) performed the pick, the quality appraisal, and the information extraction of the studies. During the selection process, a Cochrane review of early on postnatal discharge from hospital for healthy mothers and term infants was found [5]. This loftier quality review (see AMSTAR evaluation in Boosted file i) included but randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in a broader population than our population of involvement. Therefore, relevant evidence was extracted from this review [five] to focus on our specific inquiry question. In addition, the update presented here considered all comparative studies whatever the pattern, published until August 2015. Non-randomised studies were included only if they described an outcome that was not previously described in a RCT. Because wellness care organisations are perpetually evolving, we limited our search to new outcomes supported by not-randomised comparative studies during the update menstruation.

The health outcomes under consideration were mortality, morbidity, hospital readmission rates for both mother and kid. Additional neonatal outcomes (jaundice and weight proceeds) and maternal outcomes (counselling and psychological function). Breastfeeding rates were also studied.

Assessment of methodological quality of evidence

The AMSTAR checklist was used for the quality appraisal of the systematic reviews [10]. The quality appraisal of RCTs and non-randomised studies was performed using the "Cochrane Collaboration'southward tool for assessing take a chance of bias" [eleven].

Statistical analyses

Categorical data were presented using risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The mean difference with 95% CI was used to report continuous data. Statistical analyses for pooling intervention effects were performed using Review Manager 5.3®.

Level of evidence

Level of evidence was categorized in iv levels (loftier, moderate, low and very low) co-ordinate to the Grade system [12].

Results

Results of the search

From the Cochrane review, ten RCTs were extracted for full text test. From those, iii trials were excluded because deliveries by caesarean section were included and results were not reported separately for vaginal deliveries [thirteen,fourteen,15].

During the update process, no systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or RCTs were found. After a first sifting based on title and abstract, sixteen not-randomised studies were retrieved for further analysis on full text [one, 2, 6, 16,17,18,xix,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Finally, ii not-randomised studies were included in our review [16, 27].

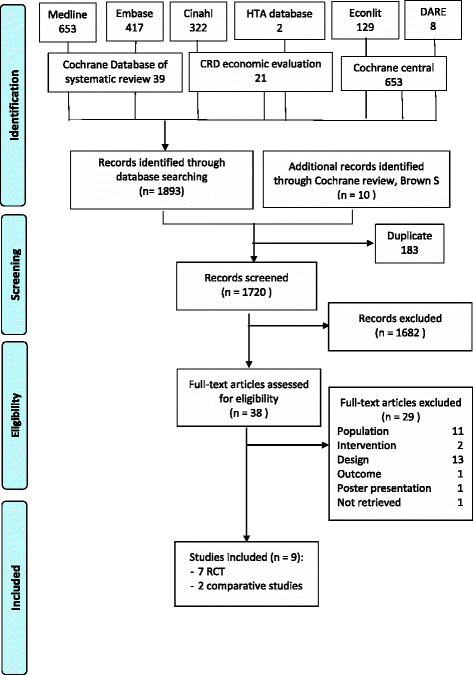

The present systematic review includes 5 RCTs and two not-randomised studies (encounter Fig. ane – Flow chart). Characteristics of the included studies are reported in Tabular array one. A list of excluded studies is provided in Additional file 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Definition of early hospital discharge

No standard definition of 'early belch' from hospital was found across trials. A variation in the discharge fourth dimension from less than 24 h to 72 h was seen. Similarly, the 'usual length of stay' ranged from 48 h to v days. In the five included trials, all early discharge programs proposed post-discharge home visits by nurses or midwives. However, prenatal preparation for early belch was not always foreseen. In the two included not-randomised studies, early discharge was defined as a length of stay of maximum 24 h. While one written report merely proposed a medical visit seven days after commitment to appraise newborn health status, the other study organised two or three dwelling house visits, during the start week, performed by two nurse-midwives with experience in neonatal care.

Early on discharge and maternal health outcomes

Morbidity

4 trials reported data on maternal morbidity [29,30,31,32]. Among these, three studies did not discover any departure in complexity rates between early discharge and conventional length of stay [29, 31, 32]. The most frequently reported pathologies were urinary tract infection, episiotomy infection, mastitis and other mammary pathologies and endometritis. In dissimilarity, Hellman et al. plant a small significant deviation in favour of conventional length of stay in comparing with early discharge in febrility, lochia, involution of the uterus, and breast engorgement at 3 weeks of puerperium [xxx]. No pooling estimation of the rate of complications was washed considering of the poor quality of information reporting and the large differences in the time frame of morbidity charge per unit measurement.

Complication charge per unit

A non-randomised study, performed in a full general hospital in Mexico, found no pregnant difference, during the first week postpartum, between reported complication charge per unit by the mothers discharged at 24 h or less and those discharged later (OR (95% CI) = 0.95 (0.41–two.twenty). In this study, the prenatal care was assessed according to the Official Mexican Norm (NOM-007-SSA2–1993) [33]. The authors found that women with an early on discharge and satisfactory prenatal care had a 64% lower odds for presenting symptoms within the first week postpartum compared with women with being discharged later on and from whom prenatal command was unsatisfactory (OR 0.36; 95% CI: 0.17–0.76) [27].

Counseling

Hellman et al. showed that mothers discharged early on were statistically significantly more likely to require more than communication during the follow-up period for themselves or for their newborn in comparison with conventional length of stay mothers [30] (see Tabular array 1). Data requested about newborns related to feeding, bowels, hygiene and care of the umbilical cord whereas breast care, perineal care, personal hygiene and practise were the most reported topics for advice for mothers.

Readmission

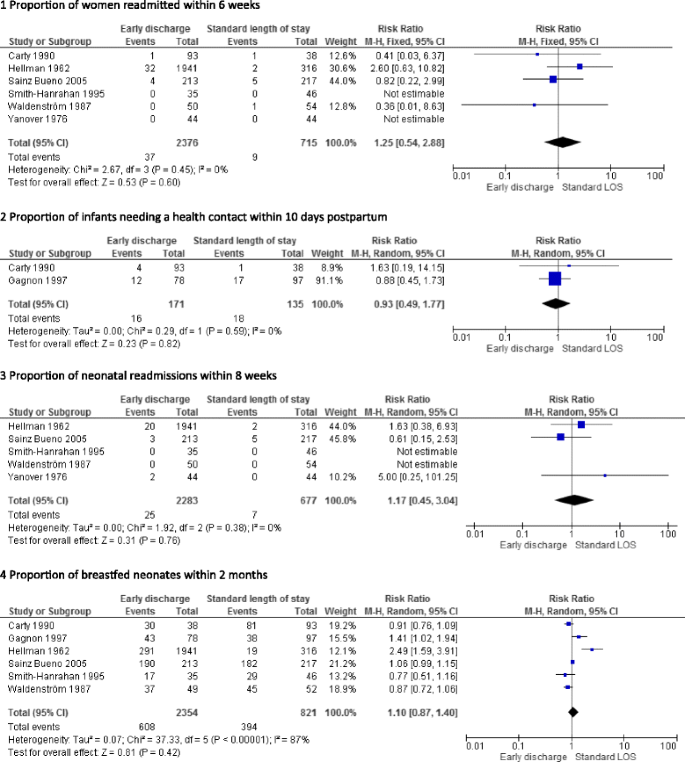

No significant differences in maternal readmission rates during the postpartum menstruation were found in four trials [29,30,31,32, 34, 35]. Figure 2 presents a pooled run a risk ratio (95% confidence interval) (RR (95%CI) of 1.25 (0.54–2.88) for maternal readmissions occurring from week 1 to vi later nascency.

Pooled estimation for maternal and neonate health outcomes

Psychological functioning

-

Depression

Carty and Bradley constitute a significant difference in mean scores on the Beck Low Index (p < 0.05) between mothers with length of stay ≤24 h and those with a 4-solar day stay (run across Table one). Mothers with a shorter postpartum stay had better emotional well-being at 1 month than those with a standard duration hospital stay. Still, no difference was found between a length of stay of 25 to 48 h and ane of 4 days [29].

Sainz-Bueno et al. showed no difference in anxiety and depression between early discharged mothers and those with conventional duration stays measured by the hospital anxiety and depression (HAD) scale [31]. All the same, it should exist noted that two.viii% of the mothers had scores on HAD scale at 1 week postpartum indicating a requirement of psychiatric monitoring. Among those, 0.5% required psychiatric admission. At i month post-commitment, this proportion reached 2.3%. All the same, no departure was constitute between early discharge and conventional stay mothers.

Waldenström et al. plant no difference in the proportions of women reporting a depressed mood during the kickoff six weeks after birth betwixt early discharge (26%) and conventional stay (34%) [35]. Reported depressed mood peaked during the 2d and 3rd week afterwards the birth.

Considering of existing differences in the scales used for measuring low, no pooling of information was performed.

-

Competence of mothering

Gagnon et al. measured competence in mothering using the Perceived Maternal Task Operation Calibration at ane month [36]. Competence in mothering included mothers' ability to assess their baby's needs and their own abilities to feed their newborn and to perform caregiving activities. The authors found no significant difference between mean scores between mothers discharged between 6 h and 36 h mail service-delivery and those discharged betwixt 42 to 72 h.

Some other randomised trial assessed women's confidence in their mothering skills using an eight-particular scale [29]. The authors reported a significantly higher score at 1 week in mothers discharged within 24 h than those discharged four days post-commitment (meet Table 1). After a month, this departure did non remain. In addition, no differences were noted between very early on discharged mothers (between 12 and 24 h) and early discharged mothers (betwixt 25 and 48 h).

-

Sense of security

Askelsdottir et al. reported a greater sense of security in the first postnatal week for early discharged women [xvi]. Even so, those women had more than negative emotions towards breastfeeding compared with women with conventional length of stay. Because in that location is no difference in parity betwixt the 2 groups, an explanation tin be found in a higher educational level of mothers included in the group with conventional length of stay. Contact between the mother, newborn and partner did not differ between the two lengths of stay.

Early belch and neonate health outcomes

Mortality

Only one trial assessed the mortality rate in newborns at 3 weeks of life [30]. The authors found bloodshed rates of 0.24% and 0.46% in newborns with early discharged conventional babies and length of stay respectively. These proportions were not statistically different.

Morbidity

Two trials reported the proportion of newborns needing a health contact within ten days postpartum [29, 36]. Pooling of results does not show any difference between early on discharged newborns and those who stayed longer in hospital after birth (run across Fig. two).

Yanover et al. ended that no significant differences in blazon or in occurrence of neonatal morbidities were observed during the follow-up catamenia [32]. Unfortunately, no data were reported. After 3 weeks, Hellman et al. did not find any significant difference in complexity rates betwixt early discharged newborns and those with conventional elapsing stays [30] (come across Table 1).

Weight proceeds

Two trials analysed the departure in weight gain of newborns with early discharge and conventional length of stay [30, 36]. The first study did not observe any significant differences in daily rates of infant weight gain during the beginning 10 days of life [36] (run into Tabular array 1). The second trial focused on weight gains at iii weeks of life [30]. No significant departure was found betwixt early discharged newborns and infants with a standard length of stay.

Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia

One trial studied the occurrence of hyperbilirubinemia [36] and reported that in that location was no divergence in identification of significant neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (see Table 1). Notwithstanding, a significantly reduced crude relative run a risk for bilirubin testing (RR [CI 95%]: 0.39 [0.17–0.94]) was observed in early on discharged neonates. Even so, the proportion of tested newborns eligible for phototherapy were not significantly unlike (RR [CI 95%]: ane.26 [0.33–four.93]).

Readmission

No significant differences in neonatal readmission rates were found in the three trials reporting information on this outcome [30,31,32, 34, 35]. The pooled RR for neonatal readmissions occurring within three to 8 weeks of birth is presented in Fig. 2 and does non show whatever increased risk of readmission in early discharged neonates.

Breastfeeding

Six trials reported data on fractional or exclusive breastfeeding from 3 weeks to nine months. Pooled estimates are presented in Fig. two and show that early discharge mothers were every bit likely to breastfeed their neonates than those with a conventional length of stay. Waldenström et al. found no difference in breastfeeding rate at 6 months according to the length of stay [35]. Sainz-Bueno et al. studied breastfeeding rates up to 9 months and did non find whatever differences between the groups at any time except at three months with a significantly higher charge per unit in early discharged mothers (see Tabular array one).

A non-randomised report reported that early belch mothers (between 12 to 24 h postpartum) described less positive emotions towards breastfeeding compared with other mothers (conventional length of stay from 24 to 48 h postpartum) [16]. Emotions towards breastfeeding were measured using the 2 domains of the Alliance calibration (Alliance calibration mean score (SD) Breastfeeding strain: early discharge: 2.4 (1.31), conventional length of stay: ane.7 (0.93); p = 0.001/Breastfeeding uncomfortable early discharge: 2.9 (ane.61), conventional length of stay: 2.ii (1.07); p = 0.028).

Quality cess of included studies and level of evidence

The only systematic review included [v] was rated at a level of 9/11 with the AMSTAR cheque list (see Additional file 1). Despite its high quality, the review was only used as a source of evidence because the research questions were slightly different with our review allowing the inclusion of caesarean sections within its scope. The quality appraisement of all RCTs matching our inclusion criteria is shown in Additional file ane. The lack of blinding of participants and personnel was not viable and was not considered a risk of bias in the context of postpartum care because it does not touch on the outcomes assessed. Methods used to ensure allocation concealment were reported in three trials [29, 31, 36] while the remaining 2 did not provided information on this methodological detail. None of the included studies indicated if outcomes assessment was blinded. In improver to the specific bias linked to their non-randomised design, the two comparative studies presented other bias such every bit single centre pattern, choice biases or small sample size. Details on quality assessment of these studies are reported in Additional file 1.

The level of evidence is documented in Boosted file 1. Despite RCT pattern, the vast majority of outcomes are rated as low or very depression level of prove. Outcomes regarding counselling, neonatal mortality rate and rate of wellness contact for newborns within ten mean solar day of life are rated equally moderate.

Give-and-take

Based on the bachelor evidence, early postpartum discharge seems to exist clinically safe for both mothers and newborns. These results are in line with a previously published review [v] which was restricted to RCTs just included caesarean sections. Early hospital belch in caesarean section deliveries did not seem to affect outcome such as breastfeeding charge per unit, maternal and babe readmission. Even so, confounders such every bit type of health system (public versus private), opportunities for antenatal grooming and for postnatal domiciliary midwife support or type of postpartum intervention cannot be studied because of poor reporting. Therefore, mixing information from vaginal delivery and caesarean section must considered with caution. Despite of this precaution, bear witness must be interpreted with circumspection for two principal reasons.

Firstly, the concept of early on hospital discharge and that of conventional length of stay varied greatly between trials, making an interpretation or comparison across studies hard. Among the selected studies, a discharge was considered early when the female parent-babe dyad was discharged from half dozen h to 72 h after birth. Currently, there are considerable variations in length of stay between Western countries. In Sweden, early discharge corresponds to a length of stay of 6 h after birth [3, 37], while in France, a discharge after a length of stay of less than 72 h is considered every bit early on [19]. In the US, a minimum period of 48 h is ensured past law after a resurgence of jaundice cases and an increase in re-admissions amidst both mothers and children [1, 2]. All the same, Evan et al. [one] demonstrated that the extension of the postpartum length of stay to 48 h had footling impact on re-admission rates for vaginally delivered newborns and was not cost saving. A lack of dwelling house postpartum follow-up may explain the absence of saving. Many Western countries already practiced early postpartum discharge for more than a decade. For these countries, what was once considered early discharge is at present a conventional length of postnatal stay. This may explicate the lack of recent published RCTs on the subject. Still, countries with longer lengths of stay such as France and Belgium may benefit from testing shorter lengths of stay in studies with an appropriate blueprint.

The second reason to interpret the findings with caution relates to the quality of the included studies. Class assessment highlighted numerous limitations in methods leading to (very) depression level of testify (see Additional file one), except for three outcomes with moderate level of evidence (counselling, neonatal mortality rate at 3 weeks, and demand for neonatal wellness contact inside 10 days). The event related to satisfaction, but reported in the RCTs, was not discussed in this systematic review because trials were performed from 10 to 39 years ago, and thus societal expectations on wellness intendance are probable to accept dramatically inverse. Amid the main methodological limitations found in the included studies were: small sample sizes that pb to bereft power, a large number of lost to follow-up, one study with poor reporting of outcomes using graphical presentation but no give-and-take on the data in numerical terms, and heterogeneity in results across studies, leading to alien conclusions.

In addition, the option criteria of study participants in RCTs were too restrictive, including well-educated women, mothers living in a stable relationship with their partners and low socioeconomic adventure, preventing the generalisation of findings to the existent world population. Pick bias was too observed in one not-randomised written report [27] because more than healthy mothers and newborns without financial difficulties were included in the early discharged group.

Besides the cautions in evidence interpretation, approximating the number of mother-babe dyads that can benefit from early belch is challenging. Yanover et al. estimated that 25% of all deliveries are eligible for early belch (i.e. after approximately 1 mean solar day). The authors used the readiness of the family unit as a necessary condition for discharge [32]. This criterion is indeed crucial for a successful early on discharge program because of a positive clan betwixt unreadiness at postpartum belch and, on the one mitt, wellness intendance use and, on the other hand, poorer health outcomes within 4 weeks after discharge [eighteen]. The readiness to be discharged tin be defined as the agreement between the mother and the medical staff (i.e. paediatrician and obstetrician) that both mother and newborn will non be likely to benefit from a longer hospital stay. If 1 of the involved parties anticipates any potential benefits for mother or infant to stay longer, the dyad is considered every bit unready [xviii].

Therefore, early belch criteria cannot but focus on clinical parameters as described in Sainz et al. [31] but should also include additional criteria regarding the prenatal preparation and the setting of home postpartum follow-upwards equally foreseen in the French guideline on early on postpartum discharge [38]. In addition, prenatal preparation, content, frequency and elapsing of abode follow-up were extremely different across studies hampering our ability to highlight best practices in these domains. In a Cochrane systematic review, the authors assessed the outcomes for women and babies of different home-visit schedules up to 42 days after nascency whatever the length of infirmary stay [39]. They ended that postnatal dwelling house visits may promote infant health and maternal satisfaction merely the frequency, timing and duration of such postnatal care visits should exist based upon local needs. As in our systematic review, an optimal packet of habitation postnatal care cannot be defined. However, several countries are developing a range of strategies to evangelize seamless individualized follow-up support using telemedicine tools such as video conferencing or apps [xl]. Nevertheless, all those strategies are unlikely to reply fully to the existing concerns most continuity of care. In addition, the shift of the follow-up tasks from hospital to home with physically or virtually nowadays carers raises concerns about medical responsibleness and legal accountability. Finally, the availability of professionals to provide the home care is an essential prerequisite for the successful transition from infirmary to postpartum dwelling house intendance without impairing the home care for other conditions [41], creating unmet needs, or using informal support workers equally doulas [42]. Due to the risk of variations in content and quality of care provided by fragmented services across multiple carers, offering a seamless transition from infirmary to home is challenging.

Toll containment is one of the drivers to endorse an early postpartum discharge policy. Just two trials included in our systematic review addressed the toll issue. In the first report implemented in the United states of america [32],the authors analysed an early discharge programme, which included 24 h hospital length of stay and daily home visits by trained nurses for iv days after birth. From a infirmary perspective, this programme provided a minimum of 30% immediate savings in daily costs versus conventional stay (48 h or more than), excluding saving generated past allocating vacated beds and rooms to other patients or purposes. The price calculation was based on expenses for salaries of nurse practitioners, paramedical personnel, and medical consultants, likewise as automobile expenses and habitation-intendance supplies. In the second study performing a price calculation from a payer perspective in Spain [31], the implementation of an early discharge programme provided savings ranging from 18 to 20% in comparison with convention infirmary length of hospital stay. This early discharge programme was made up of a less than 48 h length of infirmary stay, 1 home visit afterwards discharge past nurses qualified in puerperal and neonatal care, a practice consultation between 7 to 10 days afterward nascence and a follow-up by telephone at 1, iii and 6 months. Past comparison, the conventional discharge plan followed the aforementioned pattern except for the length of stay, which was longer than 48 h and the absence of habitation visits. The cost calculation took into account costs related to length of hospital stay, maternal – neonatal readmission, maternal – neonatal consultations, maternal – neonatal reassessment at 1 week and costs related to telephone follow-upward. Toll containment due to the implementation of an early discharge policy is highly dependent on the perspective taken into account as well equally on the blazon of health insurance system in place.

Estimation of possible toll savings cannot be performed without developing well designed RCTs including costs data collection. The collection of cost data must exist designed to accept into account non just infirmary or payer perspectives, but also the societal perspective. In addition, the hidden costs for new mothers created by a potential shift from publicly funded hospital motherhood care to private home-based postpartum care must exist advisedly scrutinized to prevent gaps in quality and accessibility of care [42].

Finally, developing quality indicators to monitor each early on postpartum discharge programme is also crucial. Quality indicator assessment allows for adjusting early postpartum belch policy when needed. Withal, the development of indicators is challenging because some indicators (due east.thou. satisfaction, overall back up, well-existence …) are qualitative and, thus more difficult to standardize [43].

Conclusions

The current available literature provides niggling scientific evidence to guide postpartum belch policy planning. The evidence based on RCTs is old, with the virtually recent trial published 10 years ago, and the quality of evidence of these trials is poor. The more recent evidence is based only on two very poor quality non-randomised studies. In addition, the concept of early on discharge itself is very variable beyond studies leading to health outcomes existence measured at variable times afterward delivery. Despite these limitations, early discharge seems to exist safe for both mother and newborn. Breastfeeding did not seem to be affected. Because of the lack of robust clinical evidence and full economic evaluations, the current data neither support nor discourage the widespread use of early postpartum belch. Before implementing an early discharge policy, Western countries with longer length of infirmary stay such equally France and Belgium may do good from testing shorter length of stay in studies with an advisable design (e.g. randomised). The issue of cost containment in implementing early belch and the potential impact on the current and future health of the population exemplifies the demand for publicly funded clinical trials in such public wellness area. Finally, trials testing the range of out-patient interventions supporting early discharge are needed in Western countries which implemented early belch policies in the past.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HAD scale:

-

Hospital anxiety and low scale

- OR:

-

Odd ratio

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

References

-

Evans WN, Garthwaite C, Wei H. Nber: the impact of early on discharge laws on the health of newborns. J Wellness Econ. 2008;27(4):843–70.

-

Fink AM. Early hospital discharge in maternal and newborn care. JOGNN. 2011;40(2):149–56.

-

Johansson K, Aarts C, Darj East. Get-go-time parents' experiences of home-based postnatal care in Sweden. Ups J Med Sci. 2010;115(2):131–seven.

-

OECD. Average length of stay: childbirth. Health: Key Tables from OECD, No. 51. 2014. doi:10.1787/l-o-s-childbirth-tabular array-2014-1-en.

-

Brown S, Modest R, Argus B, Davis PG, Krastev A. Early postnatal discharge from hospital for healthy mothers and term infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD002958.

-

De Luca D, Carnielli VP, Paolillo P. Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and early discharge from the maternity ward. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168(nine):1025–30.

-

Danbjorg DB, Wagner L, Clemensen J. Practice families after early postnatal discharge need new ways to communicate with the hospital? A feasibilility study. Midwifery. 2014;thirty(6):725–32.

-

Larsson B, Larsson Chiliad, Chantereau 1000, Staël von Holstein M. International comparisons of patients' views on quality of intendance. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 2005;18(ane):62–73.

-

Moher K, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items fir systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the Prisma argument. PLoS Med. 2009;half dozen(half dozen):e1000097.

-

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson Northward, Hamel C, Porter AC, Tugwell P, Moher D, Bouter LM. Evolution of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2007;7:10.

-

Higgins .JP.T, Light-green South (editors): Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version five.1.0 [updated March 2011]; 2011.

-

Balshem HHM, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–half dozen.

-

Boulvain M, Perneger TV, Othenin-Girard 5, Petrou S, Berner Thousand, Irion O. Home-based versus infirmary-based postnatal care: a randomised trial. BJOG. 2004;111:807–13.

-

Brooten D, Roncoli M, Finkler S, Arnold 50, Cohen A, Mennuti M. A randomized trial of early hospital discharge and home follow up of women having caesarean nativity. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(v):832–8.

-

Winterburn Due south, Fraser R. Does the duration of postnatal stay influence chest-feeding rates at one month in women giving birth for the commencement fourth dimension? A randomized control trial. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(5):1152–7.

-

Askelsdottir B, Lam-de Jonge West, Edman Yard, Wiklund I. Dwelling care after early belch: impact on salubrious mothers and newborns. Midwifery. 2013;29(8):927–34.

-

Barker K. Cinderella of the services - 'the pantomime of postnatal intendance'. Br J Midwifery. 2013;21(12):842.

-

Bernstein HH, Spino C, Lalama CM, Finch SA, Wasserman RC, McCormick MC. Unreadiness for postpartum discharge following good for you term pregnancy: impact on health intendance apply and outcomes. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(1):27–39.

-

Cambonie Thousand, Rey V, Sabarros S, Baum TP, Fournier-Favre South, Mazurier Eastward, Boulot P, Picaud JC. Early postpartum discharge and breastfeeding: an observational written report from France. Pediatr Int. 2010;52(ii):180–6.

-

Chanot A, Semet JC, Arnaud C, Dali-Youcef A, Abada Chiliad, Gayzard B, Lancelin F, Pax-Chochois S, Alves N, Curat AM et al: L'hospitalisation a domicile apres une sortie precoce de maternite. Soins 2009, Pediatrie, Puericulture.(246):24–26.

-

Chanot AA, Semet JC, Arnaud C, Dali-Youcef A, Abada K, Gayzard B, Lancelin F, Pax-Chochois S, Alves N, Curat AM, et al. Sorties precoces de maternite et hospitalisation a domicile: experience ariegeoise. Archives de Pediatrie. 2009;xvi(vi):706–8.

-

De Carolis MP, Cocca C, Valente East, Lacerenza Southward, Rubortone SA, Zuppa AA, Romagnoli C. Individualized follow upwards programme and early belch in term neonates. Ital J Pediatr. 2014;twoscore:lxx.

-

Farhat R, Rajab Yard. Length of postnatal hospital stay in healthy newborns and re-hospitalization following early discharge. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3(3):146–51.

-

Ghedin BS, Cancelier ACL, Feuerschuette OHM, Silveira SK. Healthy newborn length of infirmary stay: influence on breastfeeding and neonatal morbidity. J Perinat Med. 2011;39(S1):159.

-

Gotink MJ, Benders MJ, Lavrijsen SW, Rodrigues Pereira R, Hulzebos CV, Dijk PH. Severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in kingdom of the netherlands. Neonatology. 2013;104(2):137–42.

-

Lain SJ, Roberts CL, Bowen JR, Nassar Northward. Early on discharge of infants and risk of readmission for jaundice. Pediatrics. 2015;135(two):314–21.

-

Ramirez-Villalobos D, Hernandez-Garduno A, Salinas A, Gonzalez D, Walker D, Rojo-Herrera Yard, Hernandez-Prado B. Early infirmary discharge and early puerperal complications. Salud Publica de Mexico. 2009;51(3):212–viii.

-

Straczek H, Vieux R, Hubert C, Miton A, Hascoet JM. Sorties precoces de maternite : quels problemes anticiper ? Athenaeum de Pediatrie. 2008;15(6):1076–82.

-

Carty Eastward. C B: a randomized, controlled evaluation of early on postpartum hospital discharge. Nascency. 1990;17(iv):199–204.

-

Hellman LM, Kohl SG. Early hospital belch in obstetrics. Lancet. 1962;i:227–33.

-

Sainz Bueno JA, Romano MR, Teruel RG, Benjumea AG, Palacin AF, Gonzalez CA, Manzano MC. Early discharge from obstetrics-pediatrics at the hospital de Valme, with domicilic follow-upwardly. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 Pt 1):714–26.

-

Yanover MJ, Jones D, Miller Doctor. Perinatal care of low-hazard mothers and infants. Early discharge with home care. Due north Engl J Med. 1976;294(13):702–v.

-

Norma Oficial Mexicana "NOM-007-SSA2–1993": Atención de la Mujer durante el Embarazo, Parto y Puerperio y del Recién Nacido. Mexico Urban center: Diario oficial de la Federación 1995.

-

Smith-Hanrahan C, Deblois D. Postpartum early on belch: impact of maternal fatigue and functional ability. Clin Nurs Res. 1995;four(ane):50–66.

-

Waldenström U, Lindmark G. Early and late discharge after infirmary nascency. A comparative written report of parental background characteristics. Scand J Soc Med. 1987;fifteen:159–67.

-

Gagnon A, Edgar L, Kramer One thousand, Papageorgiou A, Waghorn G, Klein MC. A randomized trial of a program of early postpartum belch with nurse visitation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(1):205–eleven.

-

Lindberg I, Christensson 1000, Ohrling K. Parents' experiences of using videoconferencing as a back up in early discharge after childbirth. Midwifery. 2009;25(4):357–65.

-

Haute Autorité de Santé: Sortie de maternité après accouchement : conditions et organisation du retour à domicile des mères et de leurs nouveau-nés In.; 2014.

-

Yonemoto Due north, Dowswell T, Nagai Due south, Mori R. Schedules for dwelling house visits in the early postpartum period. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;seven.

-

Danbjorg DB, Wagner L, Kristensen BR, Clemensen J. Intervention among new parents followed up by an interview study exploring their experiences of telemedicine subsequently early on postnatal discharge. Midwifery. 2015;31(six):574–81.

-

Cusack CL, Hall WA, Scruby LS, Wong ST. Public health nurses' (Phns) perceptions of their role in early postpartum discharge. Tin J Public Health. 2008;99(3):206–eleven.

-

Benoit C, Stengel C, Phillips R, Zadoroznyj M, Berry Due south. Privatisation & marketisation of post-birth care: the hidden costs for new mothers. Int J Equity Wellness. 2012;11:61.

-

Escuriet R, White J, Beeckman Yard, Frith L, Leon-Larios F, Loytved C, Luyben A, Sinclair M, van Teijlingen E, EU COST Activeness IS0907, et al. Assessing the functioning of maternity care in Europe: a critical exploration of tools and indicators. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:491.

Acknowledgements

Koen Van den Heede (PhD) and Jillian Harrison, KCE, for reviewing the concluding typhoon.

Funding

The enquiry was funded past KCE (Belgian Healthcare Knowledge center). The funding torso played no role in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Search strategy, methodological quality assessment of the bear witness, list of excluded studies and grading of evidence are provided every bit additional materials.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

NB led the formulation and pattern of the study, acquired the data, analysed and interpreted the data, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, revised critically and edited all versions. LSM made substantial contributions to the formulation and pattern of the study, acquired the data and reviewed critically the manuscript for intellectual content. CD fabricated substantial contributions to the conception and pattern of the study and reviewed critically the manuscript for intellectual content. NF designed the search strategy and reviewed critically the manuscript for intellectual content. WC made substantial contributions to the conception and pattern of the written report, acquired the data and reviewed critically the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate were not needed because of the written report blueprint (literature review).

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Publisher'south Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Boosted file

Additional file 1:

Additional materials report detailed search strategy by database, assessment of the evidence using AMSTAR and Cochrane risk of bias tools, listing of excluded studies including full references and level of evidence using GRADE system. (DOCX 125 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/one.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Benahmed, N., San Miguel, 50., Devos, C. et al. Vaginal delivery: how does early hospital discharge affect mother and kid outcomes? A systematic literature review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 289 (2017). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12884-017-1465-7

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1465-7

Keywords

- Postpartum

- Early belch

- Delivery

- Mother

- Children

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-017-1465-7

0 Response to "Average Hospital Stay to Have a Baby in 1940"

Post a Comment